March 2008 – Volume 2 – Issue 5

Pages 1, 3, 6, 7, 38, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 125, 132, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 148.

__________________________________________

Page 3

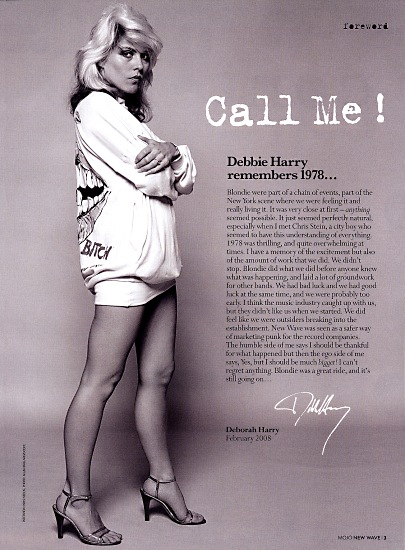

forward

Call Me!

Debbie Harry remembers 1978…

INTERVIEW: KRIS NEEDS, PHOTO: ALLAN BALLARD/SCOPE

Blondie were part of a chain of events, part of the New York scene where we were feeling it and really living it. It was very close at first – anything seemed possible. It just seemed perfectly natural, especially when I met Chris Stein, a city boy who seemed to have this understanding of everything. 1978 was thrilling, and quite overwhelming at times. I have a memory of the excitement but also of the amount of work that we did. We didn’t stop. Blondie did what we did before anyone knew what was happening, and laid a lot of groundwork for other bands. We had bad luck and we had good luck at the same time, and we were probably too early. I think the music industry caught up with us, but they didn’t like us when we started. We did feel like we were outsiders breaking into the establishment. New Wave was seen as a safer way of marketing punk for the record companies. The humble side of me says I should be thankful for what happened but then the ego side of me says, Yes, but I should be much bigger! I can’t regret anything. Blondie was a great ride, and it’s still going on…

Deborah Harry

February 2008

__________________________________________

Pages 6 & 7

THE SPIRIT OF ’78

Emboldened by punk rock, 1978 was all about new bands, new sounds and hit singles, lots of hit singles. Kieron Tyler on the birth of New Wave.

NEW WAVE CRASHED THROUGH THE door opened by punk. As 1977 rolled around, it was clear that the spirit of ’76 had inspired a music that shared punk’s vitality, stylisation and directness, but wasn’t so confrontational.

Crucially, this less abrasive sound didn’t deny the past, and had more obvious chart potential.

Short hair, concise, energetic songs, a narrow tie, straight-leg trousers, a ’60s jacket and influence or colourful clothes: all were New Wave. Rock journos at the time applied the tag willy nilly, but what else could the music be called?

In truth, New Wave and punk had always been indivisible. Nick Kent’s NME review of The Ramones’ debut album in May 1976 described the leather-jacketed foursome as “champions of the New York New Wave”.  October 1976’s issue of Mark Perry’s Brit-punk fanzine was titled Sniffin’ Glue And Other Rock’n’Roll Habits For The New Wave. When bandwagon jumpers The Vibrators issued one of the first UK punk singles, We Vibrate, in 1976 – two weeks before Anarchy In The UK – the NME’s review tarred them as “the tackiest New Wavers”.

October 1976’s issue of Mark Perry’s Brit-punk fanzine was titled Sniffin’ Glue And Other Rock’n’Roll Habits For The New Wave. When bandwagon jumpers The Vibrators issued one of the first UK punk singles, We Vibrate, in 1976 – two weeks before Anarchy In The UK – the NME’s review tarred them as “the tackiest New Wavers”.

Of course, there’d already been many New Waves. In 1960 the term was applied to the style of French film; in 1964, to a new breed of literary science fiction writers. A snappy phrase, it was inevitably co-opted for music. The Who’s first manager, Pete Meaden, called his 1967-era production company New Wave Music.

Ten years later, for XTC’s Andy Partridge, “New Wave was very silly, the soft option. I thought of French cinema and it was hardly appropriate applying the phrase to music. I didn’t like being called punk, though, we were just a pop group. New Pop would have been more appropriate.”

But New Wave it was, and reinvention was rife. “We’d play these out-of-the-way places and the support bands looked the way they did the week before,” recalls Partridge. “But they were shouting the lyrics, not singing, and had their flares taken in. They’d always say, ‘We’re not punk mate, we’re New Wave.'”

The Police snuck in, despite the inclusion of the ex-drummer of college-circuit prog rockers Curved Air and a guitarist who’d passed through Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, The Animals and Soft Machine. Pre-punk, Ian Dury’s Fagin-like persona with Kilburn And The Highroads had influenced John Lydon. But in 1977, after punk had re-acclimatised the music biz to such mavericks, Dury returned with a new band, The Blockheads, and Sex And Drugs And Rock And Roll, a song based on Ornette Coleman’s The Face Of The Bass. Dury was New Wave by default and perfect for those who found punk’s usual ramalama a little too much.

Elvis Costello was another lower-tier pub rocker retooled to fit in with the new directness: the suit jacket, drainpipe jeans, late ’50s specs, Doc Marten’s shoes, Billy Idol sneer and punchy songs were bang on. In March 1977, Record Mirror called Costello’s first single, Less Than Zero, “New Wave rock”. Costello wasn’t keep in the tag, however, despite coining his label Stiff Records’ slogan, Surfing On The New Wave.

OTHER BANDS THAT HAD COME UP CONCURRENT with punk were more comfortable with the New Wave label. “The Only Ones were definitely a part of the New Wave,” admits their bassist Alan Mair. “New Wave was very descriptive of what was happening at the time. I was totally fed up with yet another dinosaur supergroup being re-formed when there was nothing super about them at all. Finally something new was happening in music, which was so necessary as the industry was on its knees.”

The return to basic musical values was equally radical in the United States, where The Knack exemplified America’s chart-friendly New Wave – a short-haired, ’60s-influenced band playing straight ahead pop-rock while sporting skinny tied and Modish suits.

“The fact that we wore skinny ties tied us to New Wave, but we were our own thing,” argues bandleader Doug Fieger.

“We never thought of ourselves as [having] any label. We thought of ourselves as a rock’n’roll band. It blew my mind when I heard the Sex Pistols, people were finally playing rock’n’roll. We played pop-rock-rockabilly, Buddy Holly was just as big an influence as anything. We didn’t realise that music had become so Balkanised. When I was growing up if you liked The Supremes, you could also like The Mothers Of Invention.”

In the end, it didn’t – and still doesn’t – matter what anyone thought. New Wave was an all-purpose description that perfectly fitted the music of the time. It’s something jarring, often garish mix’n’match was inevitable after punk. The anything-goes, everyone’s-got-a-chance ethos of what became the New Wave echoed the DIY outlook of 1976. The B-52’s, Blondie, Squeeze, The Undertones, The Only Ones et all were an attractive, bright and irresistible New Wave, sweeping out the old and riding straight into the charts.

__________________________________________

Page 38

BLONDIE IS THE NAME OF A BAND

blondie

ALL THIS AND MORE – AVAILABLE NOW.

__________________________________________

Pages 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75,

In the flesh

Blondie came from the twilight world of New York’s underground clubs to conquer the charts, a journey that encompassed Andy Warhol, punk, hip hop, pop and more. Kris Needs recalls six years in the eye of the Blondie hurricane…

SEPTEMBER 15, 1978, Birmingham. Blondie are on blistering form tonight. Despite screams of adulation, on-stage gremlins took the shine off last night’s gig in Manchester. Tonight Blondie fire out future classics such as  Hanging On The Telephone with boundless energy and top-of-the-game confidence, singer Debbie Harry a whirling dervish dressed all in yellow, from her socks to the T-shirt given her by a fan.

Hanging On The Telephone with boundless energy and top-of-the-game confidence, singer Debbie Harry a whirling dervish dressed all in yellow, from her socks to the T-shirt given her by a fan.

There’s only one problem: the audience, which remains resolutely seated. Despite the group’s ever-more animated antics and Debbie trying to turn the chorus to the hit single Denis into a chant of “Ali! Ali! in honour of that night’s boxing bout between Muhammad Ali and Leon Spinks, nobody is dancing, or even standing. Watching from the wings, it’s not hard to notice concerned glances shooting between the band members, who normally thrive on crowd craziness.

A sortie around the hall reveals a squad of hefty, bow-tied, white-jacketed security men enforcing the signs in the foyer warning that the show will be stopped if anyone stands while the main act is on stage. The crowd is clearly straining at the leash, needing just one word of encouragement from the band who are oblivious to these restrictions.

Finally, a shout of “Come on!” from guitarist Frank Infante and Debbie’s beckoning wave during Youth Nabbed As Sniper breaks the dam; the crowd rise to its feet and rush forward like a human tsunami. It’s so sudden the bow ties are caught unawares and rendered powerless as the no-man’s-land void in front of the stage becomes a sea of outstretched hands and delirious upturned faces.

“That’s better,” cries Debbie, kicking off One Way Or Another before climaxing with riotous encores of T.Rex’s Get It On and the New York Dolls’ Jet Boy. Drummer Clem Burke strides through his kit to hurl a snare drum into the crowd, an excited Nigel Harrison hits himself in the eye with his bass, Jimmy Destri humps his keyboards and  guitarist Chris Stein can be seen basking in the requisite shower of spit raining down from the punks in the audience.

guitarist Chris Stein can be seen basking in the requisite shower of spit raining down from the punks in the audience.

As a visibly relieved band walks off, a deafening “Blondieee!” chant envelops the hall, continuing out into New Street where the band’s police-escorted tour coach forces a crowd of hundreds to part like The Red Sea. Pandemonium erupts when Debbie throws her bouquet out of the coach window. Tonight’s rather symbolic breakthrough confirms that Blondiemania has hit the UK, transcending punk, New Wave or any genre. It is one of those wonderful occasions when a rock band knows, in a moment of stunning clarity, that it’s cracked the elusive it and life will never be the same again.

Momentum had been building, but it took the craziness of September 1978’s tour to convince Blondie that after two years of hard graft and harder knocks they’d finally taken the UK. The world had a new, old-fashioned superstar – an enigmatic, Hollywood pin-up figure fronting a fervently innovative punk-pop group. Like all great bands, Blondie came with a raft of business nightmares, foot-shooting intra-band conflicts and commercial kamikaze missions. Like that era’s other giants The Clash, Blondie were often ripped into by the then-dominant music papers that could make or break careers. Zigzag, the magazine I edited for five years from 1977, loved  Blondie from the first single and said it loud until they split in 1982. Now they sit, next to The Clash, in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame hailed as all-time greats. It wasn’t always like that…

Blondie from the first single and said it loud until they split in 1982. Now they sit, next to The Clash, in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame hailed as all-time greats. It wasn’t always like that…

Deborah Harry was born on July 1, 1945 in Miami but adopted at three months by a couple that ran a gift shop in Hawthorne, New Jersey. While dreaming she was Marilyn Monroe’s lost love child, Harry had a typical suburban childhood, singing in the church choir, cheerleading and dressed down by her mother who “didn’t contemplate a future for me other than marriage”.

In 1965, after two years at finishing school, Debbie followed her artistic leanings by moving to New York, experiencing Manhattan’s bohemian revolution, Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground blow-outs and the psyched-up Fillmore East. “I was a baby growing up in the middle of this incredible scene,” she recalled.

Harry play percussion with various experimental groups including the First National Unaphrenic Church And Bank, before joining baroque folk-rockers Wind In The Willows, and singing on their only album in 1968. After the group split she embraced heroin for three years. “I was completely out of my mind. I was into junk, I was really fucked up… I wanted to blank out my mind and whole sections of my life.”

Supporting herself waitressing at Max’s Kansas City, Harry served drinks to musical heroines Janis Joplin and

Grace Slick, and Andy Warhol’s circus, including crazed musician Eric Emerson (“I made it with Eric in a phone booth upstairs,” she recalls.) This lasted eight months until she briefly ran off to California with a millionaire (“It seemed like a good idea at the time… it was something I’d always wanted to do”) then spent nine months working as a Playboy bunny. Eventually, she ended up sharing a house in Harlem with a drug dealer, which “really finished me on the whole trip. These 40-year-old guys with guns and infections all over their bodies… I just quit.”

To escape the drug lifestyle, she moved to an artistic community near Woodstock before drifting back to her parents’ house, attending beauty school and teaching exercises in a health spa. Desperate to sing again and drawn back to Manhattan by the glam-rock commotion surrounding the New York Dolls at the Mercer Arts Centre, Debbie fell into the new glitter scene, befriending Elda Gentile, whose band Pure Garbage had just split. Together with Rosie Ross, they started The Stillettoes in 1973 as a vehicle for their girl group-trash obsessions.

ENTER CHRIS STEIN, WITHOUT WHOM THE Blondie phenomenon would never have happened on such a diverse and fascinating scale. Stein was Debbie’s rock, keeping her positive once the world went Blondie crazy. With a wide knowledge of pop culture and underground art, he would also prove to be her perfect creative foil.

Born in Brooklyn on January 5, 1950, Stein immersed himself in the mid-’60s Greenwich Village folk scene, playing with local groups including The Morticians and First Crow In The Moon, whose career peak was opening for The Velvet Underground. After spending 1967’s Summer of Love tripping in San Francisco, he returned to New York, flipping out in early ’69 and spending three months in an asylum. On release he studied photography at the School of Visual Arts.

Chris was also drawn to the Mercer Arts Centre in 1972, meeting Eric Emerson, joining his band the Magic Tramps, and moving into his Lower East Side apartment. One night in October ’73, they decided to check out The Stillettoes who were playing their first gigs at the Boburn Tavern on 28th Street, where the stage was a pool table with its legs sawn off. Backed by a male drummer and guitarist, the girls mixed Shangri-Las and Supremes decked out in cave-girl outfits or ’50s-style swimsuits, under the directing of Warhol’s friend Tony Ingrassia.

Debbie later spoke of the “dark, intense stare” and immediate “psychic connection” with Stein, although they didn’t speak at first. After Elda asked him to join the band they grew closer until Chris moved into Debbie’s Thompson Street apartment. The couple bounced off each other creatively, writing songs together, including Platinum Blonde.

Debbie later spoke of the “dark, intense stare” and immediate “psychic connection” with Stein, although they didn’t speak at first. After Elda asked him to join the band they grew closer until Chris moved into Debbie’s Thompson Street apartment. The couple bounced off each other creatively, writing songs together, including Platinum Blonde.

By May ’74, Amanda Jones had replaced Linda Ross while The Stilletoes’ rhythm section comprised bassist Fred Smith and drummer Billy O’Connor. This line-up debuted at Bowery bar CBGB’s, supporting another new band called Television on their reputation-building Sunday night residency. Along with Wayne County and Suicide, these were the first bands to play what became New York’s punk epicentre. A month later, the Stillettoes received their first UK press mention when Melody Maker’s Roy Hollingsworth reviewed a gig at infamous 4th Street drag bar Club 82 alongside a photo of “… a cuddly platinum blonde called Debbi [sic]… Some of the songs were well worth putting on vinyl.”

Shortly after, Debbie quit the Stillettoes, and played CBGB’s twice under the name Angel And The Snake, before

re-naming the group Blondie after blonde singers Julie and Jacky joined. Apart from being “a street name I got from truck drivers… Blondie was a comic coming to life… I wanted to create this character who was primarily having fun.”

At first the group was a camp, Labelle-influenced romp, but Julie and Jacky quit after the latter dyed her hair brown. Cue the arrival of guitarist Ivan Kral, but he left to join Patti Smith in early ’75. An intense period of recruitments and defections followed (Fred Smith would replace Richard Hell in Television), before Blondie’s line-up stabilised around Harry, Stein, Clement Burke, an 18-year-old powerhouse drummer who worshipped Keith Moon, and his jamming mate, bassist Gary Valentine.

Blondie established an HQ/domicile at a converted doll factory, reportedly haunted by poltergeists, three blocks from CBGB’s. It was squalid, even by Bowery standards. A visiting Wayne County was “shocked when I found someone had shit in their sink”. The transsexual titan recalls seeing Blondie at “an old run-down Irish bar, set up on the floor, and all these old drunks were stumbling by going, ‘Yeah baby, shake it honey’.” Debbie worked as a waitress at White’s pub near Wall Street, daydreaming songs such as In The Flesh and Die Young Stay Pretty.

In June, NME’s Lisa Robinson reported on CBGB’s, mentioning Debbie’s “appealing trashiness”. Local writer Alan Betrock briefly became Blondie’s manager, paying them to record demos of Platinum Blonde, Thin Line, Puerto Rico and Once I Had A Love – The Disco Song, plus the Shangri-Las’ Out In The Streets. When Suicide’s Marty Rev turned them down, student doctor Jimmy Destri became Blondie’s newest recruit, arriving with his distinctive Farfisa organ.

MEANWHILE, THE BLONDIE MALES’ IMAGE RECEIVED a mod makeover when Burke returned from England with the first Dr Feelgood album. “If there’s one group that could take credit for giving direction to the New York scene it must be Dr Feelgood,” said Debbie, who continued developing her Blondie character assisted by

designer friend Stephen Sprouse, including a zebra-skin dress made from pillow-cases found in the garbage.

However, by late ’75, with Patti Smith and The Ramones signed to major labels, Blondie still felt like “the band least likely to” and were further depressed when another NME round-up declared: “Sadly Blondie will never be a star simply because she ain’t good enough.”

The tide turned in February 1976 when now-former manager Alan Betrock launched a bi-monthly scene lifeline, New York Rocker, featuring the group’s first full-length interview and declaring, “They are geared for war; an all-out assault on NYC.” Blondie was always a great idea; now they were growing into it. The group appeared regularly in Punk magazine, the Mutant Monster Beach Party photo-strip depicting Debbie and Joey Ramone as star-crossed lovers. It was a vibrant period, captured in Amos Poe’s documentary Blank Generation, with Blondie filmed at CBGB’s performing Platinum Blonde and He Left Me. The band also supplied the music for Vain Victory, Jackie Curtis’s Tony Ingrassia-directed play in with Debbie appeared as chorus girl Juicy Lucy.

Blondie were the surprise hit of the Max’s Easter Festival. Appearing alongside Wayne County, Pere Ubu, Suicide, The Heartbreakers and The Ramones, they impressed ’60s girl-group producer Richard Gottehrer who’d just started a production company called Instant Records with former New York Dolls manager Marty Thau. After grabbing Blondie for a single, they signed the band to Frankie Valli’s Private Stock label.

In August, Blondie recorded their self-titled debut album at Plaza Sound Studio, a room built for Stravinsky at

New York’s Radio City Music Hall. The first single [Se]X Offender was released in November, its title changed due to record company pressure. Based on a true story about a sex offender who falls for her arresting officer, it spliced a classic girl-group sound with a Farfisa-driven punk energy. UK music paper Sounds made it Single Of The Week.

The album appeared in January 1977, unselfconsciously mixing garage rock, New York pop and Doors/Jefferson Airplane influences. Creem declared, “This is the band that’s sure to put Gotham City on the map.” A month later, former Wind In The Willows manager Peter Leeds took over Blondie’s affairs as they hit Los Angeles for a week-long stint at the Whisky A Go-Go, followed by another week playing with The Ramones. Phil Spector invited Blondie to his Hollywood fortress, to discuss producing their next album. A loose jam session ensued, where Spector unnerved them by interrogating anyone daring to ask when they could leave.

Impressed, David Bowie invited Blondie to support Iggy Pop on the US tour for Iggy’s The Idiot album. Iggy and Bowie ensured the group were looked after, but not all support tours would be so easy…

May 31, 1977

Bristol

It’s the last night of Blondie’s first UK tour, and they’re winning over both the punks and hippies at Bristol’s Colston Hall with a cover of The Doors’ Moonlight Drive. Debbie is pretty in pink, almost preppy, with skinny tie and ponytail, bouncing and high-kicking into the rabble-rousing Kung Fu Girls and a new Iggy tribute Detroit 442.

It’s enough to secure an encore of Ronnie And The Daytonas’ Little GTO, introduced by Gary Valentine taking a wrong turn and plunging several feet off the side of the stage. After Blondie’s spark, headliners Television are self-indulgent, like someone’s forgotten to turn them on.

For the London music press crew – Sniffin’ Glue’s Mark Perry and Danny Baker, NME’s Tony Parsons and myself – Blondie rule. The group, however, are annoyed at Television who, fired by glowing album reviews and record  company backing, consigned them to lowly support status.

company backing, consigned them to lowly support status.

Suffering endless sound problems, Blondie were panned by journalists taken to the show by Television’s record company, but the reception was warmer by the following week’s Hammersmith Odeon gig. “We’re disappointed that the press is misinterpreting us,” Debbie sighs. “They did it to us in the States, and it took a while to catch on. We get encores at every single show and the press puts us down. It’s unbelievable.”

After Hammersmith we meet Chris and Debbie at Bailey’s Hotel. They were already in bed but Chris let us in, Debbie protecting her modesty with a sheet. Instantly friendly, they invited me to an upcoming show in Bristol.

The Blondie boys are amiable enough and boisterous in typical American rock band on the road fashion. Everyone insists that “Blondie Is A Group” (even having T-shirts made up with the slogan), but although they all contribute to the sound, it’s Harry’s striking high profile and Stein’s ingenious strategies that will be their passport to fame.

At this vital stage, where other groups would spotlight their best assets, Blondie do the opposite, downplaying their singer in order to keep the peace. I can sense their paranoia when repeatedly asked if we’re using a photograph of the whole band as an image on the Zigzag cover. Rumblings of dissent will occur whenever Debbie gets a magazine front cover for the next five years. Ultimately this jealousy will play a major part in Blondie’s demise.

Finally, though, here’s Debbie in the flesh. On first meeting, it’s easy to be disarmed by the unearthly gaze. In conversation, her voice can take on a mellifluous sing-song quality, or switch between razor street tones and silky-toned angel, always tempered with a streak of playful surreal humour. I later find out that she is shy and reserved until she gets to know someone. Chris is her spiritual counterpart who loves to expound with a dry wit on anything from conspiracy theories to comic books.

Blondie initially had difficulty making headway in the punked-up UK, where old-fashioned beauty was shunned by the likes of Siouxsie, Gaye Advert and The Slits. Over a year earlier Debbie had declared, “I want to do something to make people change the way they think and act towards girls.” She was furious when Private Stock printed a promotional poster featuring her in a see-through blouse (“It’s not selling us in the right way”). This tour showed they were all fighting the same cause. “Girls come up to me and say, ‘Great, keep going, do it.’ I’m not making enemies of girls, I’m making fans of girls.” Ultimately, Harry would be the most subversive of all: a sex symbol with brains, bringing the noir-ish underground of NYC to Top Of The Pops.

In Bristol, Debbie talked about the band name while preparing to go on-stage. “It’s an easy name to remember and sort of descriptive. I’ve been stuck with blonde hair for three years but I’m getting tired of it. You get tired of bleaching your hair out. I’ve always had different coloured hair, but to try to stop it now…” Realising that might be somewhat untimely, Harry steels herself to the current mission and warns, “We’ll be back! We’re flying over with bombs!”

After returning to New York, Peter Leeds fired bassist Gary Valentine, the group claiming he was becoming to difficult with his spotlight-hugging antics. Another friend of Clem Burke’s, Frank ‘The Freak’ Infante took his place as Blondie returned to Plaza Studios with producer Richard Gottehrer for six weeks to record their second album. Valentine had objected to covering Randy And The Rainbows’ Denis but bequeathed them I’m Always Touched By Your (Presence Dear), both prime singles material. Debbie wanted to shake off the nostalgia tag and inject some “high voltage rock” into the music. With a noticeable maturity in the songwriting, the trademark Blondie sound was now in place.

The album cover picture was shot in New York. Debbie posed on a rented cop car, wearing a pink dress that she’d sewed herself from a pattern created by her friend Anya Phillips. The album’s title, Plastic Letters, came from the shop sign captured in the background.

During the album’s recording, Peter Leeds negotiated a bigger record deal with Chrysalis, buying out Private Stock for half a million dollars. A 25-date November UK tour was whittled down to just three shows as European interest increased when the first album’s bitch-fest Rip Her To Shreds single took off. Meantime, Infante switched to guitar, making way for new bassist Nigel Harrison, who’d previously played in glam-rockers Silverhead and Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek’s Nite City.

Blondie’s first gig was at Friars in Aylesbury, my local venue. After the quirky prog-pop of the support act, a new group from Swindon called XTC, the near-capacity crowd howled with appreciation as a new, improved Blondie stormed through the first-album tracks and a cover of The Runaways’ I Love Playing With Fire, Debbie strutting the stage in transparent black blouse and leather trousers. Local legend has it that my then-wife discovered me backstage in a drunken clinch with Ms Harry, halfway up a ladder. Oops.

The subsequent London Rainbow Theatre show was less successful, suffering from poor sound and with the group appearing overawed by the larger stage. The promised bombs had yet to drop but the Friars gig demonstrated that Blondie certainly had the potential to become the biggest of all the New Wave bands.

Scoring a surprise Australian hit with In The Flesh, Debbie submitted to a two-week media blitz down under, debunking punk and fuelling rumours that she tore her clothes off during Rip Her To Shreds, ensuring packed houses on the ensuing tour.

January 24, 1978,

Dingwalls, Camden, London

Blondie are launching their 1978 offensive with an invite-only gig to whip up media interest in the imminent release of Plastic Letters. The new year seems to have brought a new attitude. The recent Sex Pistols split has hammered the last nail in punk, leaving the music business desperately searching for a new trend. Blondie find themselves figureheads of what the press have dubbed ‘power pop’, a smarter-dressed alternative to punk, which the music business finds easier to handle.

The band have clearly returned at the right time. Zigzag’s first Blondie piece of 1978, fronted by a photograph Stein donated from the famous zebra-girl picture session, described a day when everything goes wrong on Blondieworld. Burke and Destri arrive at Dingwalls with the news that Stein has come down with ‘flu. Infante and Harrison turn up alongside Debbie – sporting a huge black leather coat, wooly hat and shades – reporting that a doctor has given Chris a mega flu-jab. Blondie are also using a new, untried PA and Kiss’s soundman, who’s unfamiliar with their set. In narrow Dingwalls, with its stage-front pillars, the soundcheck is a feedback-drenched din. Nothing bodes well for the show.

Accompanying the group to Kensington’s Royal Garden Hotel, Debbie says Chris wants to see me. Propped up in bed, looking like death although the fever has passed, Stein feels terrible but will play the gig: “I’ll just wear shades and be cool.” While Debbie takes a bath, Chris shows me his photos taken on their world tour. As we talk, Debbie potters around, getting ready for the gig, settling on an outfit of short denim jacket and gold boots. She inevitably turns heads as we stroll past through the lobby, brandy bottle in hand, “in case I catch Chris’s flu”.

Dingwalls is teeming with liggers and journalists. Blondie drift on, Chris propping himself against one of the pillars, and kick into X Offender, while battling against the feedback. The cacophony has the crowd wincing and on-stage tensions rising. The sound improves as the set progresses, notably a crashing version of The Rolling Stones’ My Obsession, but Blondie are visibly rattled. Before the encore, Burke starts playing too soon and Stein  pulls him up on it. The drummer trashes his kit and storms past Destri. “Er, goodnight,” shrugs Debbie before shuffling off. Backstage, insults and punches are thrown, in a scene later likened by Debbie to a movie brawl, with Burke and Destri squaring up to each other. The fight spills out into the yard and has to be broken up by bouncers. Not a good night.

pulls him up on it. The drummer trashes his kit and storms past Destri. “Er, goodnight,” shrugs Debbie before shuffling off. Backstage, insults and punches are thrown, in a scene later likened by Debbie to a movie brawl, with Burke and Destri squaring up to each other. The fight spills out into the yard and has to be broken up by bouncers. Not a good night.

The following month, though, new single Denis hits Number 2 in the UK charts and Blondie return, this time with maximum firepower. It’s exhilarating, almost shocking to watch the unbridled adulation at Dunstable Civic Hall and London’d Roundhouse, Debbie on-stage sporting a white mini-dress and knee protectors (to the delight of backstage guest, Motörhead’s Lemmy). Music press reviews now trumpet the group’s “vast potential” and Harry’s “real stage presence”.

Returning home, Blondie found they were still broke, exacerbating an already deteriorating relationship with manager Peter Leeds, not helped when Leeds announced that everyone in the band could be replaced. Punk-fearing US radio stations still weren’t playing Blondie’s records, so Debbie and Chris toured America charming DJs, distributors and record store reps, who repeatedly told them they needed “the right song”.

In June, ultra-tight from touring, Blondie checked into New York’s Record Plant to make their third album. Producing was Mike Chapman, the brains behind ’70s glam titans such as Mud, Sweet and Suzi Quatro. A perfectionist who demanded endless takes, Chapman honed Blondie into a pop hit machine. “It’s good, light listening,” Chapman declared. “That’s what Blondie’s all about.”

Named after an unfinished Harry song, Parallel Lines was studded with such gems as “our fake Motown song” Pretty Baby, 11.59, Stein’s exquisite Sunday Girl and The Disco Song, now reactivated and titled Heart Of Glass. Cover versions included Jeffrey Lee Pierce’s recommendation of Californian singer Jack Lee’s Hanging On The Telephone. The album consummated Blondie’s friendship with King Crimson guitarist and Eno collaborator Robert Fripp, who elevates Stein’s ravishing sci-fi love song Fade Away And Radiate, originally written in 1974. New York Rocker would declare Parallel Lines “one of the most inspiring records of the last five years”, while the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau placed it “as close to God as pop-rock albums ever get, or got”.

Meanwhile, though, the group moaned about the now iconic album sleeve. Peter Leeds had told the group they could pick their individual images, then chose the solitary smiling shot. Blondie made moves to extricate themselves from the manager they said “treated us like kids”.

After a July US tour supporting The Kinks, Blondie were back in the UK. Zigzag predicted a riot as the group swept the annual readers’ poll, Harry beating Patti Smith for Female Singer and everybody for Sexiest Person.

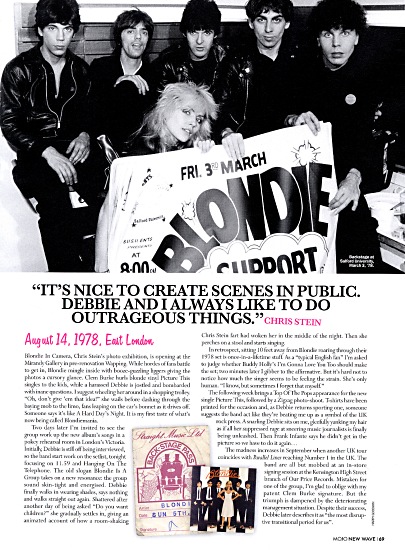

August 14, 1978, East London

Blondie In Camera, Chris Stein’s photo exhibition, is opening at the Mirandy Gallery in pre-renovation Wapping. While hordes of fans battle to get in, Blondie mingle inside with booze-guzzling liggers giving the photos a cursory glance. Clem Burke hurls blonde vinyl Picture This singles to the kids, while a harassed Debbie is jostled and bombarded with inane questions. I suggest wheeling her around in a shopping trolley. “Oh, don’t give ’em that idea!” she wails before dashing through the baying mob to the limo, fans leaping on the car’s bonnet as it drives off. Someone says it’s like A Hard Day’s Night. It is my first taste of what’s now being called Blondiemania.

Two days later I’m invited to see the group work up the new album’s songs in a pokey rehearsal room in London’s Victoria. Initially, Debbie is still off being interviewed, so the band start work on the setlist, tonight focusing on 11.59 and Hanging On The Telephone. The old slogan Blondie Is A Group takes on a new resonance: the group sound skin-tight and energised. Debbie finally walks in wearing shades, says nothing and walks straight out again. Shattered after another day of being asked “Do you want children?” she gradually settles in, giving an animated account of how a room-shaking Chris Stein fart had woken her in the middle of the night. Then she perches on a stool and starts singing.

In retrospect, sitting 10 feet away from Blondie roaring through their 1978 set is once-in-a-lifetime stuff. As a “typical English fan” I’m asked to judge whether Buddy Holly’s I’m Gonna Love You Too should make the set; two minutes later I gibber to the affirmative. But it’s hard not to notice how much the singer seems to be feeling the strain. She’s only human. “I know, but sometimes I forget that myself.”

The following week brings a Top Of The Pops appearance for the new single Picture This, followed by a Zigzag photo-shoot. T-shirts have been printed for the occasion and, as Debbie returns sporting one, someone suggests the band act like they’re beating me up as a symbol of the UK rock press. A snarling Debbie sits on me, gleefully yanking my hair as if all her suppressed rage at sneering music journalists is finally being unleashed. Then Frank Infante says he didn’t get in the picture so we have to do it again…

The madness increases in September when another UK tour coinsides with Parallel Lines reaching Number 1 in the UK. The band are all but mobbed at an in-store signing session at the Kensington High Street branch of Our Price Records. Mistaken for one of the group, I’m glad to oblige with my patent Clem Burke signature. But the triumph is dampened by the deteriorating management situation. Despite their success, Debbie later describes it as “the most disruptive transitional period for us”.

It’s September 14, 1978 and we’re back in Manchester. The plan is for yours truly to spend two days in the eye of the hurricane of Blondie’s UK tour, accompanying them, as Chris Stein now puts it, “into the hinterlands of Britain as we lived out our fantasies of Beatlemania”. Arriving at Manchester’s Britannia Hotel, the group are gathered in a room watching themselves play Picture This on Top Of The Pops. An hour later they’re sitting in a Manchester Free Trade Hall dressing room waiting for the night’s show to start. Debbie starts out quiet and withdrawn, gradually loosening up as the day goes on. As the group tunes up, she clowns around and sings, getting psyched up for showtime.

IN EVERY CITY THE KIDS HAVE HAD THEIR tickets for weeks, and Debbie’s face can be seen pouting on badges pinned to a thousand lapels. In Manchester, Harry arrives on-stage, yells “Surf’s up!” and they’re off with In The Sun followed in rapid succession by X Offender and songs from all three albums, energy levels stoked by rabid fans clambering on shoulders and throwing gifts. I’m Gonna Love You Too stops the show, before Denis ups the mayhem quotient. Fade Away is the big set piece, with Debbie wearing a mirrored gown that sends dazzling light beams into the crowd. She drops the gown for the final home stretch, bookended with Pretty Baby and Kung Fu Girls.

The stage invaders are hilarious: boys leaping up, kissing Debbie, raising their arms in triumph, and then jumping straight back into the mêlée. Debbie teases, dancing sporadically, touching outstretched hands and evoking memories of Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust performance from some years earlier. Tonight’s encores are Rip Her To Shreds, Return Of The Giant Ants, Get It On and Jet Boy.

Unbelievably, Blondie aren’t happy after the show, bickering in the dressing room about the sound – and personal problems. They find they’re in a minority when they try to leave the venue. Several hundred teenagers clamour around the Apollo’s stage door, screaming like an eerie swarm of bees. I’m standing next to Debbie in the small backstage entrance, waiting for the right moment to hop the few feet onto the coach. Getting the nod from the tour manager who positions himself as a one-man human shield, Debbie pulls down her baseball cap and smiles. “You ready? Here goes.” It’s barely yards between the door and the coach but seems more as we run a gauntlet of grabbing hands, one whipping the cap off Debbie’s head, much to her annoyance, as it had her Jilted John badge stuck to it.

The three minute drive to the Britannia Hotel finds us accompanied by most of the Apollo’s audience, with fans pounding on the side of the coach, howling, “Blondieee!… Debbieee!” Is it like this every night. She shakes her head. “Oh, last night was much worse!”

The following night is the aforementioned Birmingham show. The post-gig mood is ebullient and relieved after the No Standing signs are pointed out. “It surprised us because we didn’t think they were getting off on it,” confesses Debbie. “It was really weird. Scary!”

“Everybody said that it kept running through their minds that they’d read the press and thought we stunk,” laughs Chris. An attempt at an interview on the drive to London degenerates into a drunken free-for-all, Debbie’s contribution peaks with, “… the music press has been really good to us, even though some of them are cunts. Cunts! Fucking cunts!” before the whole thing decends into a mass sing-along of Loch Lomond. Clem Burke is in heaven. “All this stuff for me is like I’m totally living out my ideal,” he insists. “Believe it or not, my Utopia is this.”

BY JANUARY 1979, ALICE COOPER’S MANAGER Shep Gordon had taken over Blondie’s affairs, the band buying themselves out of yet another naive business deal. Heart Of Glass became Blondie’s first Number 1 single. Mike Chapman had spent hours constructing the electronic beat on a Roland rhythm machine, adding percolating synths and guitars topped with Debbie’s downtown Donna Summer sass to create a sublime electro-pop song that mirrored New York’s underground club scene.

Back in ’74, while the New York Dolls scene had bustled at the Mercer Arts Centre, nearby clubs such as the Loft were shaping modern DJ, clubbing and 12-inch remix culture, worlds apart from the crass commercialisation which swept the world after Saturday Night Fever. Nevertheless, releasing a disco song was a brave move in a year when the ‘Disco Sucks’ backlash climaxed with that July’s burning of 10,000 dance records in a Chicago park. Despite Debbie’s view that Heart Of Glass was “one of the most innovative songs Blondie ever recorded”, long-time fans and art-scene friends were openly hostile, accusing the band of “selling out”. “We did it because we wanted to be uncool,” countered Debbie. “I always thought people who categorised us as nostalgia, punk or anything were out of their minds.”

Heart Of Glass proved to be a smart move as, finally, DJs previously suspicious of Blondie’s punk connections  started playing the single, including the extended 12-inch mix, while TV stations aired a promo video filmed at chic Studio 54 alternative New York New York. Draped in a sheer, silver Sprouse dress, Debbie sang through gritted teeth, while the boys cavorted with mirror balls. Heart Of Glass topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. By early ’79, Blondie were the biggest group in Europe. Having spent 18 months cracking the continent, it was time to tour the US to capitalise on the single’s success there – and make a fourth album. Britain wouldn’t see Blondie again until the end of the year.

started playing the single, including the extended 12-inch mix, while TV stations aired a promo video filmed at chic Studio 54 alternative New York New York. Draped in a sheer, silver Sprouse dress, Debbie sang through gritted teeth, while the boys cavorted with mirror balls. Heart Of Glass topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. By early ’79, Blondie were the biggest group in Europe. Having spent 18 months cracking the continent, it was time to tour the US to capitalise on the single’s success there – and make a fourth album. Britain wouldn’t see Blondie again until the end of the year.

In the US, Blondie made the cover of Rolling Stone accompanied by the headline Riding The Crest Of The New Wave. The interview lumped them in with new British acts The Police and Dire Straits. “New Wave sounds more like the name of a laundry detergent,” complained Harry. Like much written about the band, thought, the tone of the article was condescendingly cynical. In May, as Sunday Girl topped the UK singles charts, Blondie recorded a fourth album, Eat To The Beat, at the Power Station with Mike Chapman. Although the quintessential Blondie sound was still present, the album struck out into new musical territory with Chris Stein’s Shayla (“a psychedelic country song in outer space”), the apocalyptic Victor and Atomic’s futuristic disco majesty.

The first single Dreaming was girl-group heaven with Brill Building songwriter Ellie Greenwich on backing vocals, and reached Number 2 in the UK in September. Surprisingly, Union City Blue, one of Blondie’s grandest urban anthems, only made Number 13 two months later.

Blondie’s long-promised UK tour took place in December 1979. A promotional whirlwind, it included another Our Price Records in-store which saw 3,000 fans jamming Kensington High Street. Stein rated this as the best thing about success. “It’s nice to go in a record store and create scenes in public because I’ve always tried to create scenes in public and Debbie has too. We always did outrageous things, so now we’re doing it on a mass level on Kensington High Street in front of traffic – and it’s fantastic.” In 2008, that one day still remains Stein’s personal Blondiemania highlight: “We stayed there for four hours signing records and greeting people. There was a moment when Debbie stuck her head out of a window on the upper floor and yelled, ‘Happy New Year!’, at the crowd who shouted back en masse. That was awesome.”

After recording Dreaming for the Christmas edition of Top Of The Pops, the UK tour started on Boxing Day at the Glasgow Apollo. In January, Blondie fought to play eight nights at the more intimate Hammersmith Odeon instead of Wembley Arena, resulting in some of their best-ever performances. Debbie described playing as “surreally effortless”. During one of the Hammersmith encores, Iggy Pop appeared for Funtime, while every show saw Robert Fripp reprising his role on Bowie’s Heroes.

The mood in the Blondie camp was noticeably lighter: they were again under new management. Previously, Harry had always been seething about Peter Leeds. But the more success they achieved, the further Blondie’s ambitions drifted from hit records and wet dreams for the masses. We had to talk…

January 31, 1980,

Carlton Towers Hotel, Knightsbridge

It’s three o’clock on a Sunday afternoon. Chris Stein and Debbie Harry have recently woken up, and a hotel breakfast is being wheeling into their suite. Debbie springs out of bed sporting the same Day-Glo striped mini-dress she’d worn on New Year’s Eve, hair tousled, face devoid of make-up. But today she radiates, especially when smiling, which is frequently. While Debbie bounces on the bed, pours coffee and hops around the room, rarely in the same place for five second, Chris sprawls barefoot, a half-smile on his face as he enthuses about the nightly Hammersmith aftershow party. Despite the punishing timetable, they seem content.

I’m not here for an official interview, although “hanging out with Needs” is on their tour itinerary, which is sweet. The last time I’d seen Blondie was during the craziness of 1978. Press reports were now painting Debbie as a fame-obsessed diva and/or virtual recluse. The day the press claimed she was imprisoned in a Birmingham hotel room, she’d been out shopping, disguised in a brunette wig, giggling at the headlines on the news-stands.

“That’s the silliest thing I’ve ever heard!” she guffaws. Today, with her sporadic buffoonery and easy chatter, she will reflect and expound with Stein about the past few years and, more excitedly, about upcoming projects. My “hanging out” turns into the longest interview they give on this tour. Today’s recurring theme is how the next Blondie album will defy expectations. But it’s less careerist scheming, more a relentless desire to let off artistic steam in the face of enormous success.

“I’ve a feeling the next album may not come out for quite a while, because we can’t do another album in the series of Blondie’s smash hits,” explains Stein. “It has to be something different. Maybe big band hits of the 1930s and ’40s.

“I’m just a little disturbed by the commercialism of the whole thing,” he adds. “Just the way that Blondie is. I think now we’re so successful we can reach people. We can still reach those kids, maybe with a different message. Something else…”

Debbie, meanwhile, wonders if life wasn’t simpler in the gutter. “It’s better to be at the bottom actually… on a certain level. It’s such a business to be on top. There’s no ethics involved, there’s no moral code. The only moral code is get what you can.”

Changing managers has made a noticeable difference in the band’s mood as, for the first time, Harry feels in charge of her destiny. “I’ve more control over what I’m doing now than ever before. I’m singing much better now.”

As usual, the mood only darkens when the music press is mentioned but Debbie even shrugs this off. “We came here for our audience. We’re not making any money, we’re doing it for the fans. It’s inevitable that part of the game is to get the press but it’s really silly. I wish that these people really had to do something of their own initiative, something creative so they could see what it’s like because they’re full of shit. Plain English, they’re full of shit.”

As I leave, Debbie starts bubbling about yet another project. “Wait until you hear the single we did with Giorgio Moroder. It’s fantastic. It’s the title song of a new movie called American Gigolo.”

“Giorgio listened to all our albums and put together the ultimate Blondie song,” adds Stein. Moroder, Donna Summer’s producer, had given Debbie an instrumental called Man Machine with instructions to sprinkle a little Blondie magic on it for the soundtrack to an upcoming film starring Richard Gere. By April, the song, now titled Call Me, would be a Number 1 in the UK and US, with a Spanish version released on the renownwed New York disco label Salsoul.

IN THE MEANTIME, BLONDIE STOPPED TOURING AND went off and tackled various side projects. Chris worked with the East Village post-punk jazz troupe Lounge Lizards; Jimmy Destri produced a compilation of unknown groups; Nigel Harrison played with his old Silverhead bandmate Michael Des Barres, while Clem Burke produced a band called The Colors. A letter from Stein, purportedly at ‘Vultures Boulevard, NY’ in a March 1980 issue of Zigzag reported that “We have been doing some guest appearances around town. We just played with The Contortions last night, Debbie introduced The Specials… We are doing a fund-raiser for Kennedy on Monday and tonight is The Clash!”

Another letter in June dispelled rumours about Blondie’s demise. “The group has not broken up, we are all alive. The weather is great, watch out for terrorists, I don’t believe in flying saucers any more (well not too much).”

Blondie were now regarded as genre-straddling godfathers of the downtown post-punk scene centred around such clubs as Hurrah, the Mudd and Danceteria. Debbie could jam with punk-jazzers such as The Contortions and appear on The Muppet Show singing One Way Or Another with frog scouts.

“The whole thing about Blondie is its expansion,” she insisted. The band approached their fifth studio album, AutoAmerican, bend on change. After Abba and Chic were discounted as producers, Moroder fell through, The Specials declined and Phil Spector was ruled out after terrifying The Ramones, Blondie decided to stick with Mike Chapman. Recording at his Los Angeles studio, they deployed a 30-piece orchestra for Stein’s cinematic theme of Europa, jazz musicians on the night-club croon of Faces, while Follow Me turned Lerner-Loewe’s Camelot ballad into a haunting space hymn.

“We very consciously wanted to go against what we’d done previously,” explained Debbie, citing the ever-changing David Bowie as a personal inspiration. It was a bold gamble lambasted by critics but loved by fans. The Tide Is High covered The Paragons’ 1965 rocksteady hit and shot to Number 1 in the UK, followed by the album reaching Number 3 in November. January ’81’s Rapture was, however, the only Blondie single to do better in the US than UK, reaching Number 1 just as Debbie prepared to record her first solo album with Chic.

In July 1981, the singer was devastated when her close friend Anya Phillips lost a two-year battle with cancer. Anya had been one of Harry’s closest confidantes since her days waitressing at White’s pub in New York. “She was a powerful energy source that’s now missing from the scene,” said Debbie. ‘Anya’s death was a particularly personal loss for us.” Soon after, Debbie and Chris left for Europe to promote KooKoo.

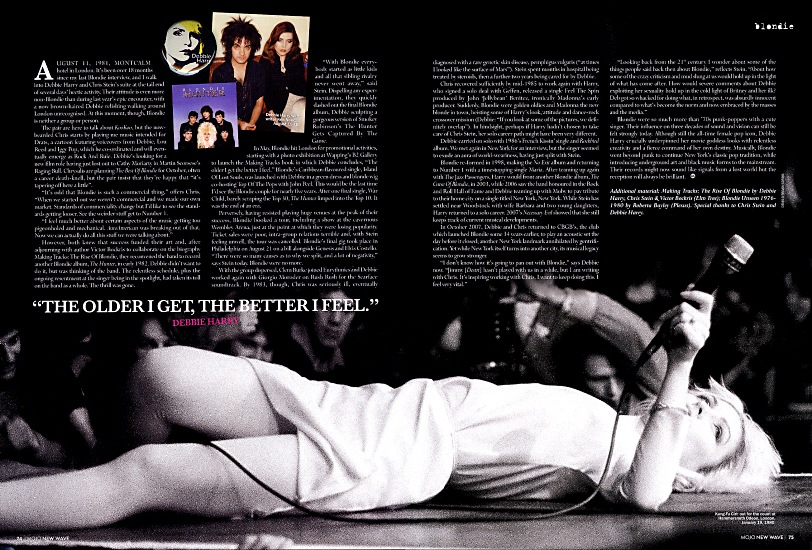

AUGUST 11, 1981, MONTCALM hotel in London. It’s been over 18 months since my last Blondie interview, and I walk into Debbie Harry and Chris Stein’s suite at the tail end of several days’ hectic activity. Their attitude is even more non-Blondie than during last year’s epic encounter, with a now brown-haired Debbie relishing walking around London unrecognised. At this moment, though, Blondie is neither a group or a person.

The pair are here to talk about KooKoo, but the now-bearded Chris starts by playing me music intended for Drats, a cartoon featuring voiceovers from Debbie, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, which he co-ordinated and will eventually emerge as Rock And Rule. Debbie’s looking for a new film role having just lost out to Cathy Moriarty in  Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. Chrysalis are planning The Best Of Blondie for October, often a career death-knell, but the pair insist that they’re happy that “it’s tapering off here a little”.

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. Chrysalis are planning The Best Of Blondie for October, often a career death-knell, but the pair insist that they’re happy that “it’s tapering off here a little”.

“It’s odd that Blondie is such a commercial thing,” offers Chris. “When we started out we weren’t commercial and we made our own market. Standards of commerciality change but I’d like to see the standards getting looser. See the weirder stuff get to Number 1.

“I feel much better about certain aspect of the music getting too pigeonholed and mechanical. AutoAmerican was breaking out of that. Now we can actually do all this stuff we were talking about.”

However, both knew that success funded their art and, after adjourning with author Victor Bockris to collaborate on the biography Making Tracks: The Rise Of Blondie, they reconvened the band to record another Blondie album, The Hunter, in early 1982. Debbie didn’t want to do it, but was thinking of the band. The relentless schedule, plus the ongoing resentment at the singer being in the spotlight, had taken its toll on the band as a whole. The thrill was gone.

“With Blondie everybody started as little kids and all that sibling rivalry never went away,” said Stein. Dispelling any experimentation, they quickly dashed out the final Blondie album, Debbie sculpting a gorgeous version of Smokey Robinson’s The Hunter Gets Captured By The Game.

In May, Blondie hit London for promotional activities, starting with a photo exhibition at Wapping’s B2 Gallery to launch the Making Tracks book in which Debbie concludes, “The older I get the better I feel.” Blondie’s Caribbean-flavoured single, Island Of Lost Souls, was launched with Debbie in a green dress and blonde wig co-hosting Top Of The Pops with John Peel. This would be the last time I’d see the Blondie couple for nearly five years. After one final single, War Child, barely scraping the Top 30, The Hunter limped into the Top 10. It was the end of an era.

Perversely, having resisted playing huge venues at the peak of their success, Blondie booked a tour, including a show at the cavernous Wembley Arena, just at the point at which they were losing popularity. Ticket sales were poor, intra-group relations terrible and, with Stein feeling unwell, the tour was cancelled. Blondie’s final gig took place in Philadelphia on August 21 on a bill alongside Genesis and Elvis Costello. “There were so many causes as to why we split, and a lot of negativity,” says Stein today. Blondie were no more.

With the group dispersed, Clem Burke joined Eurythmics and Debbie worked again with Giorgio Moroder on Rush Rush for the Scarface soundtrack. By 1983, though, Chris was seriously ill, eventually diagnosed with a rare genetic skin disease, pemphigus vulgaris (“at times I looked like the surface of Mars”). Stein spent months in hospital being treated by steroids, then a further two years being cared for by Debbie.

Chris recovered sufficiently by mid-1985 to work again with Harry, who signed a solo deal with Geffen, released a single Feel The Spin produced by John ‘Jellybean’ Benitez, ironically Madonna’s early producer. Suddenly, Blondie were golden oldies and Madonna the new blonde in town, heisting some of Harry’s look, attitude and dance-rock crossover mission (Debbie: “If you look at some of the pictures, we definitely overlap”). In hindsight, perhaps if Harry hadn’t chosen to take care of Chris Stein, her solo career path might have been very different.

Debbie carried on solo with 1986’s French Kissin’ single and Rockbird album. We met again in New York for an interview but the singer seemed to exude an aura-of-world-weariness, having just split with Stein.

Blondie re-formed in 1998, making the No Exit album and returning to Number 1 with a timestopping single Maria. After teaming up again with The Jazz Passengers, Harry would front another Blondie album, The Curse Of Blondie, in 2003, while 2006 saw the band honoured in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Debbie teaming up with Moby to pay tribute to their home city on a single titled New York, New York. While Stein has settled near Woodstock with wife Barbara and two daughters, Harry returned to a solo career. 2007’s Necessary Evil showed that she still keeps track of current musical developments.

In October 2007, Debbie and Chris returned to CBGB’s, the club which launched Blondie some 34-years earlier, to play an acoustic set the day before it closed; another New York landmark annihilated by gentrification. Yet while New York itself turns into another city, its musical legacy seems to grow stronger.

“I don’t know how it’s going to pan out with Blondie,” says Debbie now. “Jimmy [Destri] hasn’t played with us in a while, but I am writing with Chris. It’s inspiring working with Chris. I want to keep doing this. I feel very vital.”

“Looking back from the 21st century I wonder about some of the things people said back then about Blondie,” reflects Stein. “About how some of the crazy criticism and mud slung at us would hold up in the light of what has come after. How would severe comments about Debbie exploiting her sexuality hold up in the cold light of Britney and her ilk? Deb got so whacked for doing what, in retrospect, was absurdly innocent compared to what’s become the norm and now embraced by the masses and the media.”

Blondie were so much more than ’70s punk-poppers with a cute singer. Their influence on three decades of sound and vision can still be felt strongly today. Although still the all-time female pop icon, Debbie Harry crucially underpinned her movie goddess looks with relentless creativity and a fierce command of her own destiny. Musically, Blondie went beyond punk to continue New York’s classic pop tradition, while introducing underground art and black music forms to the mainstream. Their records might now sound like signals from a lost world but the reception will always be brilliant.

Additional material: Making Tracks: The Rise Of Blondie by Debbie Harry, Chris Stein & Victor Bockris (Elm Tree); Blondie Unseen 1976-1980 by Roberta Bayley (Plexus). Special thanks to Chris Stein and Debbie Harry.

__________________________________________

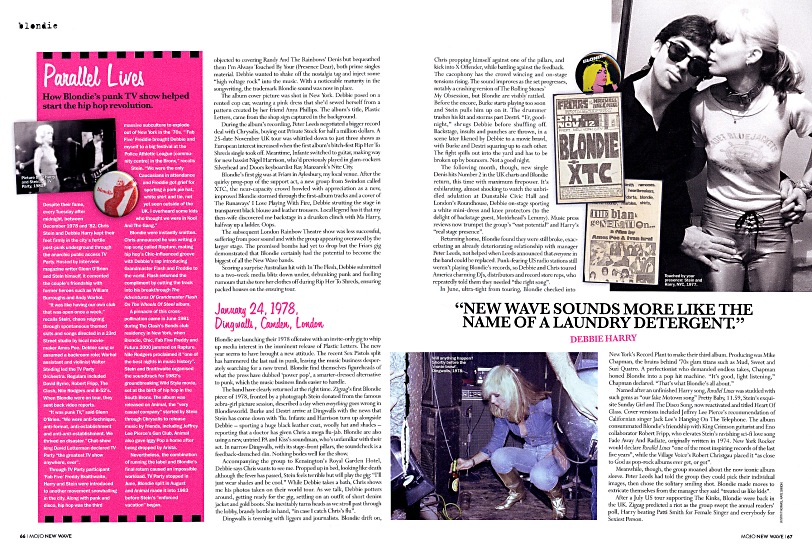

Parallel Lives

How Blondie’s punk TV show helped start the hip hop revolution

Despite their fame, every Tuesday after midnight, between December 1978 and ’82, Chris Stein and Debbie Harry kept their feet firmly in the city’s fertile post-punk underground through the anarchic public access TV Party. Hosted by Interview magazine writer Glenn O’Brien and Stein himself, it cemented the couple’s friendship with former heroes such as William Burroughs and Andy Warhol.

“It was like having our own club that was open once a week,” recalls Stein, chaos reigning through spontaneous themed skits and songs directed in a 23rd Street studio by local moviemaker Amos Poe. Debbie sang or assumed a backroom role; Warhol assistant and violinist Walter Steding led the TV Party Orchestra. Regulars included David Byrne, Robert Fripp, The Clash, Nile Rodgers and B-52’s. When Blondie were on tour, they sent back video reports.

“It was punk TV,” said Glenn O’Brien. “We were anti-technique, anti-format, anti-establishment and anti-anti-establishment. We thrived on disaster.” Chat-show king David Letterman declared TV Party “the greatest TV show anywhere, ever”.

Through TV Party participant ‘Fab Five’ Freddy Braithwaite, Harry and Stein were introduced to another movement snowballing in the city. Along with punk and disco, hip hop was the third massive subculture to explode out of New York in the ’70s. “‘Fab Five’ Freddie brought Debbie and myself to a big festival at the Police Athletic League [community centre] in the Bronx,” recalls Stein. “We were the only Caucasians in attendance and Freddie got grief for sporting a pork pie hat, white shirt and tie, not yet seen outside of the UK. I overheard some kids who thought we were in Kool And The Gang.”

Blondie were instantly smitten. Chris announced he was writing a rap song called Rapture, mating hip hop’s Chic-influenced groove with Debbie’s rap introducing Grandmaster Flash and Freddie to the world. Flash returned the compliment by cutting the track into his breakthrough The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel album.

A pinnacle of this cross-pollination came in June 1981 during The Clash’s Bonds club residency in New York, when Blondie, Chic, Fab Five Freddy and Futura 2000 jammed on Rapture. Nile Rodgers proclaimed it “one of the best nights in music history”. Stein and Braithwaite organised the soundtrack for 1982’s groundbreaking Wild Style movie, set at the birth of hip hop in the South Bronx. The album was released on Animal, the “very casual company” started by Stein through Chrysalis to release music by friends, including Jeffrey Lee Pierce’s Gun Club. Animal also gave Iggy Pop a home after being dropped by Arista.

Nevertheless, the combination of running the label and Blondie’s final return caused an impossible workload. TV Party stopped in June, Blondie split in August and Animal made it into 1983 before Stein’s “enforced vacation” began.

__________________________________________

Pretty Baby

How Debbie Harry’s first solo album skewered her public image.

The combination of Blondie’s perfect pop tones and Chic’s symphonic disco seemed like a musical marriage made in heaven. Yet Debbie Harry’s debut solo album, KooKoo, shunned both bands’ trademark sounds and alienated her following with its controversial sleeve.

Released in August 1981, the album was Debbie’s chance to work with Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards, Stein’s original choice of producers for Blondie’s AutoAmerican. Chic had already broken away from dance music with their own darkly cynical Rebels Are We, while Stein and Harry wanted to continue the black music crossover started in Blondie’s Rapture.

While Blondie were recording Eat To The Beat at NY’s Power Station studios, they met Chic who were finishing an album with Diana Ross. “We had all that stuff in common with Rapture, which was really a homage to Chic,” said Stein. “We started getting more of a black audience in the States and that crossed over.”

Recorded that Spring, Harry-Stein and Rodgers-Edwards wrote four songs apiece and two as a group for KooKoo. Rodgers’ favourites Devo sang backing vocals. “It really was fun to do,” giggled Debbie. “My face would hurt from laughter.”

For the sleeve shot, Debbie allowed H.R. Giger, the monster creator for the film Alien, to airbrush Brian Aris’s portrait with skewers representing earth, air, fire and water. It was a desecration of the Blondie image and was banned by London Transport who feared it was “likely to disturb children and old people”.

KooKoo was launched with a jungle-themed party at Sanctury, the women-only fitness centre in London’s Covent Garden. Debbie, in green wig and kimono drank one Perrier and left “looking tired and distressed”, according to The Sun. KooKoo crossed over in the US and made the UK Top 10.

__________________________________________

Touched By Her Presence

Five band that were once tipped to be the next Blondie.

THE TOURISTS

The Tourists (top left) finally hit in 1979 with a cover of Dusty Springfield’s I Only Want To Be With You. Frustrated by the sub-Blondie jibes, singer Annie Lennox and partner Dave Stewart reinvented themselves as Eurythmics, whose first album featured Blondie’s recently ex-drummer Clem Burke.

THE REZILLOS

Sire Records thought they’d found the UK’s answer to Blondie in Edinburgh’s Rezillos, with singer Fay Fife frugging through B-movie trash anthems such as Flying Saucer Attack. After scoring a 1978 hit with Top Of The Pops, the group clashed with their label and supernova’d into The Revillos (now re-formed with original name and members).

THE MOTELS

Singer Martha Davis had been around the block and already had two teenage daughters by the time Capitol picked up The Motels (top right) in 1979. In ’83, four albums in and Blondie gone, they finally cracked the US Top 10 with Suddenly Last Summer. Davis currently runs a new Motels.

THE PHOTOS

Fronted by brunette ex-hotel receptionist Wendy Wu, this Evesham-based band were a classic New Wave tale, forming from punk group Satan’s Rats and signed to CBS. Tony Visconti produced their 1980 debut album, which hit the Top 10 amid a barrage of Blondie comparisons, not least because of the Plastic Letters-style cover.

THE GUN CLUB

From the moment he clapped eyes on Debbie Harry in 1977, Jeffrey Lee Pierce was smitten. He started running the Blondie fan club, and by 1980 had formed The Gun Club, resembling Debbie’s little demon brother with his own peroxide mane. In 1982, Chris Stein released The Gun Club’s album, Miami, on his own Animal Label. Debbie sang backing vocals as D.H. Lawrence. Sadly, Blondie’s greatest fan died of a brain haemorrhage in 1996.

__________________________________________

Page 76

PICTURE THIS

As Punk became New Wave and ’78 rolled into ’79 and beyond, Blondie, Pretenders, Buzzcocks, The Police and more brought musical vitality and a visual spark into the charts. New sounds and a new look…

DEBBIE HARRY

BY MARTYN GODDARD

Here, the Blondie queen bee assumes a Marilyn Monroe pose. By ’78 and third album Parallel Lines, Blondie had moved from the scuzzy NY punk underground into the charts. Harry’s past life as a model made her a gift for rock photographers everywhere.

__________________________________________

Pages 125 & 132

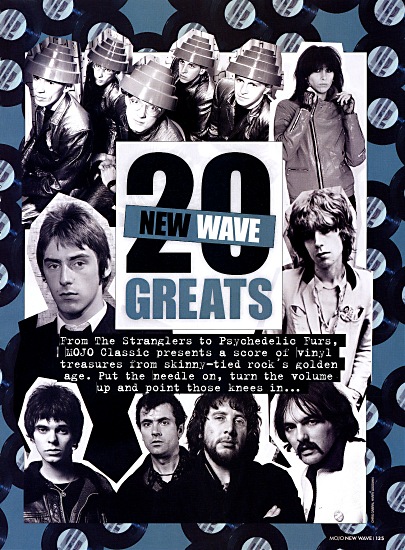

20 NEW WAVE GREATS

From The Stranglers to Psychedelic Furs, MOJO Classic presents a score of vinyl treaures from skinny-tied rock’s golden age. Put the needle on, turn the volume up and point those knees in…

Parallel Lines

BLONDIE

(CHRYSALIS, SEPTEMBER 1978)

“New Wave sounds like a hairstyle,” grumbled Malcolm McLaren, getting to the crux of the phenomenon. In place of punk rock’s untutored playing and shambolic look, New Wave offered an altogether more proficient music and a coiffeured, photogenic and, above all, sexy package. In 1978, Debbie Harry was already 33, yet she became the New Wave pin-up, displaying echoes of the filmic beauty of Marilyn Monroe but with a feistier edge.

Blondie’s debut album, and the 1977 follow-up Plastic Letters (which included two major UK singles in Denis and I’m Always Touched By Your Presence, Dear), established the band in Australia and the UK, but it was their third album, Parallel Lines, which – in an unlikely scenario for the runt of the CBGB’s litter – was a global smash. “They  went from being The Band Least Likely To Succeed to signing to Chrysalis,” recalls Blondie’s first producer, Craig Leon. “Everyone was jealous. None of the other bands had hits, apart from Patti [Smith] with Because The Night.”

went from being The Band Least Likely To Succeed to signing to Chrysalis,” recalls Blondie’s first producer, Craig Leon. “Everyone was jealous. None of the other bands had hits, apart from Patti [Smith] with Because The Night.”

For Parallel Lines, the band chose Mike Chapman as producer. He and songwriting partner Nicky Chinn had established themselves as the UK’s top pop gurus, with a host of undemanding if fun singles for the likes of Sweet, Suzi Quatro, Mud and Smokie. Together they wrote one such song, Some Girls, which would be held back in reserve should Blondie’s own material fall short. It soon became apparent that the song (later a massive hit for Racey) would not be required. With Picture This, One Way Or Another, Heart Of Glass and Sunday Girl, Blondie had written the most commercial songs of their career.

Chapman’s job was to tighten things up. “It was all over the place musically,” he later said. “Clem [Burke] had this attitude that he was Keith Moon and just wanted to play every drum all of the time. It was a real challenge to convince them that the early demo of Heart Of Glass was out of tune and out of time.”

The re-tuned Blondie had more pop discipline. Harry’s vocals were tauter and, taken as a whole, Parallel Lines has more hooks than any other New Wave record, as demonstrated by the sing-along Pretty Baby and the cover of the power pop obscurity Hanging On The Telephone.

Yet there’s also a darker side to help balance the mood. Chris Stein’s Fade Away And Radiate features deft contributions from guitarist Robert Fripp. Lyrically, too, there were some unexpected twists. Picture This is a song about lust and surveillance, while the US single, One Way Or Another, is, according to Harry, “about a fucking stalker, a potential serial killer, motherfucker rapist and the song’s going di-di-da-da, bouncin’ around. That was a nice sick touch. I would hate to be all light and buoyant.”

But it would be one song, Heart Of Glass, that packed the killer punch. A disco/New Wave crossover, and the third single from Parallel Lines, Heart Of Glass became the band’s first UK Number 1 in early 1979, selling 1,180,000 copies. Significantly, it also topped the US charts and, finally, made Blondie a transatlantic phenomenon.

DAVID BUCKLEY

__________________________________________

Pages 142 & 143

I GET WILD – USA

More songs about fictitious dances, feminine wiles and sexual neurosis. Twenty killer New Wave tracks from the US.

CHOSEN BY DON WALLER.

Dreaming

BLONDIE

Fronted by Debbie Harry, NYC’s Blondie was the archetypal New Wave group, all skinny-ties, twangy guitars and Farfisa organ, but it’s Clem Burke’s manic, Keith Moon-struck drumming that turns the track into perfection.

HEAR IT ON: EAT TO THE BEAT

(CHRYSALIS, 1982)

__________________________________________

Pages 144 & 145

WIN! A LIMITED EDITION SIGNED PRINT PLUS ELVIS COSTELLO CDS

Feeling lucky, punk? Then have a stab at our New Wave crossword.

Rockarchive brings to light rare/unseen/unpublished images by the world’s best rock photographers and prints them to the very highest standard. Currently celebrating their 10th anniversary, Rocharchive have donated this exclusive print of Debbie Harry to MOJO Classic. Photographed for the cover of Blondie’s Denis single in 1977, this high-quality fine-art A3 print comes signed by photographer Sheila Rock.

Five runners-up will also receive a set of three deluxe edition Elvis Costello CDs: My Aim Is True, This Year’s Model and Armed Forces, courtesy of the lovely people at Universal Records.

__________________________________________

Page 146

the final word

“HERE I WAS, LIVING THE LIFE. WHAT COULD BE BETTER THAN THAT?”

DEBORAH HARRY

__________________________________________

Back page 148

NEW WAVE SPECIAL 1978

30TH ANNIVERSARY

BLONDIE

THE UNTOLD STORY

1978 AND BEYOND

NEW INTERVIEWS

PREVIOUSLY UNSEEN PICTURES

THE GREATEST ALBUMS, SONGS AND MORE

PLUS WIN A SIGNED DEBBIE HARRY PRINT!