December 2019

Page 3

CONTENTS

66 DEBBIE HARRY

The Blondie singer has told her own story at last: adoption, acid, punk, Bowie’s junk, the secrets and lies. But why did it feel like pulling teeth?

Pages 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71

“I CREATED THIS PERSONA WHO WAS, TO A DEGREE, Myself”

FOR DECADES, BLONDIE’S DEBBIE HARRY SAW VERSIONS OF HERSELF REFLECTED IN THE MIRRORS OF THE MEDIA AND HER AUDIENCE. TELLING HER OWN VERSION OF HER STORY – INCLUDING THE HEROIN, CHRIS STEIN’S ILLNESS AND DAVID BOWIE’S PENIS-FLASHING – WAS AN ORDEAL THAT MADE HER RETCH, BUT SHE’S COME THROUGH IT WITH “CLARITY” ENHANCED. “I KNOW I WAS LUCKY,” SHE TELLS DAVID FRICKE. “AND I STILL AM.”

FOR DECADES, BLONDIE’S DEBBIE HARRY SAW VERSIONS OF HERSELF REFLECTED IN THE MIRRORS OF THE MEDIA AND HER AUDIENCE. TELLING HER OWN VERSION OF HER STORY – INCLUDING THE HEROIN, CHRIS STEIN’S ILLNESS AND DAVID BOWIE’S PENIS-FLASHING – WAS AN ORDEAL THAT MADE HER RETCH, BUT SHE’S COME THROUGH IT WITH “CLARITY” ENHANCED. “I KNOW I WAS LUCKY,” SHE TELLS DAVID FRICKE. “AND I STILL AM.”

DEBORAH HARRY WALKS INTO THE ROOM AS IF LITTLE HAS changed since 1976. It is a typical mid-summer day in New York City, gruesomely hot and sultry, and the production office at SIR Studios is a tiny, claustrophobic mess. But the singer and defining face of Blondie takes a seat with cool, natural glamour: at once playfully girlish and regally minimalist, dressed entirely in queen-of-the-night black except for a shocking-pink baseball cap. Harry is partly hiding behind large, tinted sunglasses, and her namesake hair is now a more sandy shade of sunlight. But whenever a smile spreads across her broad, distinctive features or her eyes light up with challenge, the effect is immediate and familiar. Just turned 74, Harry is still a beautiful and commanding presence – with a deep seasoning of age and experience.

She has just come out of a rehearsal down the hall with the current line-up of Blondie, still anchored by Harry, guitarist Chris Stein – her co-founder and ex-partner – and drummer Clem Burke. The Bowery-born punk institution – which broke up in 1982 after five years as CBGB’s biggest international success story and is more than two decades into a second era of touring and recording – is about to go on the road with Elvis Costello And The Imposters. One of the first shows is in Forest Hill, Queens – strolling distance from where Harry’s old friends, the four original Ramones, grew up.

“Those boys – I can’t believe they’re all gone,” she says wistfully. “It brings tears to my eyes.” Harry pauses, her thoughts turning to another lost soul from Blondie’s scuffling years. “Chris and I have a saying – we wonder what  Johnny Thunders would be doing now, what kind of songs he would be writing.”

Johnny Thunders would be doing now, what kind of songs he would be writing.”

In fact, Harry is here to talk about something she has just written: her autobiography. Based on interviews with MOJO’s Sylvie Simmons with additional essays by the singer, Face It is Harry’s long dive back into a wildly colourful life of extremes – adolescent hippy adventure; hard-won pop celebrity; the eternal battle to be taken seriously as a woman in an oppressively male circus – that she often found physically painful to revisit. “It wasn’t like I was jumping for joy,” Harry confesses. “There were times when I would go, ‘Do I have to?'” She makes a retching sound as if sick to her stomach. “It took a couple of years to drag it out of me.”

But revelation comes right away as Harry opens the extraordinary circumstances of her birth – in Miami as Angela Trimble on July 1, 1945 – and her adoption by a New Jersey couple, Richard and Cathy Harry. Drawing on long-sealed records, the singer’s reconstruction of her birth parents’ saga – lovestruck teens separated by the girl’s parents; a reunion years later, a surprise pregnancy and final separation – rolls like a late-’70s Bruce Springsteen ballad. Escaping placid middle-class life for New York in the mid-’60s, Harry takes LSD for the first time in the company of Timothy Leary; serves the famous as a waitress at Max’s Kansas City; and attends Woodstock with a close friend from childhood, the singer Melanie.

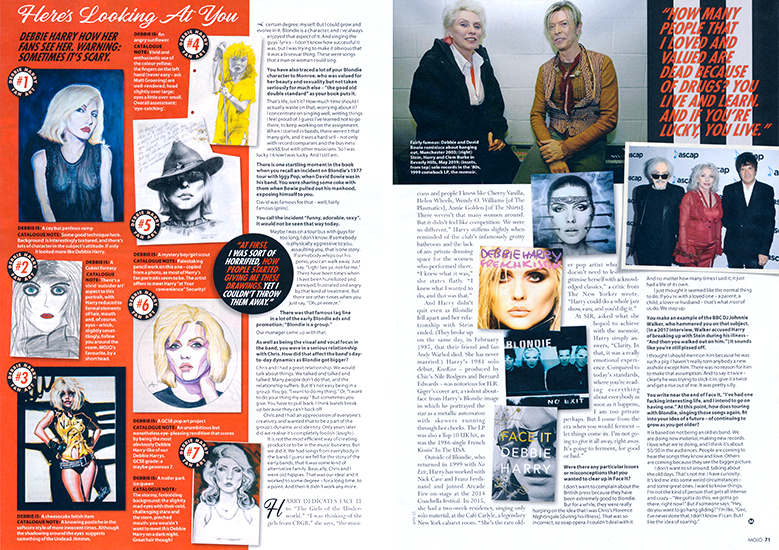

There is forensic examination of Blondie’s chaotic origins, the road to fame and cornerstone singles such as X Offender, the group’s bracing pop-noir debut in 1976, and 1981’s Rapture, the first US Number 1 with rap vocals. Harry is also candid about her extended dalliance with heroin and the difficult years following Blondie’s bitter collapse, including her time caring for Stein after their split as he fought pemphigus vulgaris, an autoimmune disease. Face It is lavishly illustrated but not in the way you expect; Harry liberally shares full-colour reproductions of the fan art she has collected on tour going back to the ’70s.

“At first, I was sort of horrified, how people started giving me these drawings,: she explains. “Yet I couldn’t throw them away. I would stick them in my suitcase. And I started appreciating how people were showing me a piece of themselves. Many of the things aren’t signed. But I always feel there is something of the person who did it in there for me to look at.

“Because I really don’t need to look at myself,” Harry adds quickly. “I look at myself entirely too often.”

The story of your birth and adoption is poignantly detailed. What was it like to learn so much about your birth parents after so long?

I knew a certain amount from my [adopted] mother. And I was always curious. But I never wanted to upset my [adopted] family, to make them think that I didn’t love them. Today, adopted children are encouraged to look up their birth parents – to know who they are, where they are; to put the pieces together. In 2017, I was allowed legal  access to the adoption agency’s records. Even then, it took a while because the records were handwritten, and they had to get it into their computers.

access to the adoption agency’s records. Even then, it took a while because the records were handwritten, and they had to get it into their computers.

But I always realised how privileged I was. My adopted family – we didn’t have a lot of money. But it was peaceful; I felt protected. That’s the thing about adoption – that separation from the mother. It is completely horrifying. You have no language, no skills for survival. I had a great fucking life. I know that anything could have happened to me when I was put up for adoption. And I was given all of this.

When did you realise you were attractive – and the value in that?

From my point of view, it was another lucky break. Why wouldn’t I enjoy being noticed and appreciated for it? It’s coin of the realm, and it takes a while to understand it. I was very shy. When I was at the awkward age, I did not think that I was pretty. I still have days like that (holds a hand to her face as if to hide). If anything, this book is a story about evolving and being the person that you want to be, not just what people see. Then when you find out what that is, you are willing to express it. And I always wanted to be an artist. I never had any doubt in my mind whatsoever.

In the book, you recall attending two New York shows in the ’60s that left a mark on you: The Velvet Underground With Nico and Janis Joplin with Big Brother And The Holding Company. Those women were polar opposites in looks and sexual authority on-stage. What did you see and admire in them?

The fact that they were doing it. At that point in my life, I was inspired by that – and terrified by it. We all have different sides to our personalities. Janis could bowl you over. But when you see somebody so strong like that, you realise there is another side in there that is so tiny, sweet and vulnerable. I served her a steak at Max’s once. I was working the table where she was sitting. But she didn’t eat it. I wrapped up her steak and took it home.

You’re frank in the book about your extended experiences with heroin, which started in the ’60s. You also mention that you took heroin in part to cope with depression.

Sure – self-medication. Most people turn to some kind of alternative state of mind. I remember one of the maitre d’s at Max’s – I was going, “I’m so tired,” and he goes, “Here.” And all of a sudden, “Oh, that was great.” Let’s face it – that was an era when not much was known about it. It wasn’t talked about the way it is now. I’m mainly shocked about what’s going on now with those pills [opioids]. My God, in this day and age when everybody knows everything, what the fuck are you doing?

Was drug use a way for you to deal with the pressures of being in Blondie?

I didn’t do it that much when I was working. When I was with Blondie, doing music, I was fine – nothing. When I wasn’t working… (affects look of distressed exhaustion). I stopped years and years ago, in the ’80s. So here I am. I learned my lesson. I loved it, I hated it – all of the above. How many people that I loved and valued are dead because of drugs? You live and learn. And if you’re lucky, you live.

BLONDIE WAS A STREET NAME I got from truck drivers – they all yell, ‘Hey Blondie!'” Harry recalled in her first-ever cover story – in May 1976 in the third-ever issue of New York Rocker. “Now,” she added, “all the bums on the Bowery yell, ‘Hey, Blondie!'”

Harry was already bleaching her hair – originally closer to chestnut-brown – to a platinum extreme when she was 14, inspired by the charisma and vulnerability of another former brunette, Marilyn Monroe. “Some people don’t respect blondes, especially bleached blonde,” Harry told MOJO in 2005. “But for me, it was a real internal shift. I loved the whole idea of dangerous innocence.” At one point in Blondie’s early days, gigging on bills in the Bowery with the Ramones and Talking Heads, Harry tried to convince the guys in her band to bleach their hair as well. The idea went nowhere.

Harry and Stein, five years her junior, first met in 1973. She was a singer in The Stilettoes, a trashy pop-art spin on ’60s girl groups; Stein had joined their backing band. He and Harry were soon a couple, starting Blondie in 1974. The New York scene was so small and casually incestuous that Fred Smith, later of Television, was  Blondie’s first bassist. In Face It, Harry notes that Clem Burke auditioned for Patti Smith’s band on the same day he answered Blondie’s Village Voice ad for a “freak energy rock drummer”.

Blondie’s first bassist. In Face It, Harry notes that Clem Burke auditioned for Patti Smith’s band on the same day he answered Blondie’s Village Voice ad for a “freak energy rock drummer”.

In that New York Rocker interview, published three months before Blondie went into the studio to record their self-titled first LP, Harry said the band was “struggling to get a sound and a style”. But she had her vision. “Rock’n’roll is a real masculine business, and I think it’s time girls did something in it,” Harry said, citing Joplin’s inspiration. “But she had to sacrifice herself. Every time she went on stage, she had to bleed for the audience. I don’t feel I have to sacrifice myself.

“The strongest art comes from the strongest people,” Harry declared. “I didn’t think I was strong enough at one time, but I do now.”

How much was Blondie – as a name and character – a burden? It was something the rest of the band couldn’t share.

I had worked with [underground theatre actor and director] Tony Ingrassia when I was in The Stilettoes. He was into Method acting, and that taught me a lot. It eased me through a certain amount of inner shyness. I got to the point where I had created this persona who was, to a certain degree, myself. But I could grow and evolve in it. Blondie is a character, and I’ve always enjoyed that aspect of it. And singing the guys’ lyrics – I don’t know how successful it was, but I was trying to make it obvious that it was a bisexual thing. These were songs that a man or a woman could sing.

You have also traced a lot of your Blondie character to Monroe, who was valued for her beauty and sexuality but not taken seriously for much else – “the good old double standard” as your book puts it.

That’s life, isn’t it? How much time should I actually waste on that, worrying about it? I concentrate on singing well, writing things I feel proud of. I guess I’ve learned not to go there, to keep working on the assignment. When I started in bands, there weren’t that many girls, and it was a hard sell – not only with record companies and the business world, but with other musicians. So I was lucky. I know I was lucky. And I still am.

There is one startling moment in the book when you recall an incident on Blondie’s 1977 tour with Iggy Pop, when David Bowie was in his band. You were sharing some coke with them when Bowie pulled out his manhood, exposing himself to you.

David was famous for that – well, fairly famous (grins).

You call the incident “funny, adorable, sexy”. It would not be seen that way today.

Maybe I was on a tour bus with guys for too long, I don’t know. If somebody is physically aggressive to you, assaulting you, that is one story. If somebody whips out his penis, you can walk away. Just say, “Ugh! See ya, not for me.” There have been times when I have been humiliated and annoyed, frustrated and angry by that kind of treatment. But there are other times when you just say, “Oh, pl-eeeeze.”

There was that famous tag line in a lot of the early Blondie ads and promotion: “Blondie is a group.”

Our manager came up with that.

As well as being the visual and vocal focus in the band, you were in a serious relationship with Chris. How did that affect the bands’ day-to-day dynamics as Blondie got bigger?

Chris and I had a great relationship. We would talk about things. We talked and talked and talked. Many people don’t do that, and the relationship suffers. But it’s not easy being in a group. You go, “I want to do my thing,” Or, “I want to do your thing my way.” But sometimes you give. You have to pull back. I think bands break up because they can’t back off.

Chris and I had an appreciation of everyone’s creativity and wanted that to be a part of the group’s dynamic and identity. Only years later did we realise it’s completely foolish (laughs).

It is not the most efficient way of creating product or to be in the music business. But we did it. We had songs from everybody in the band. I guess we fell for the story of the early bands, that it was some kind of alternative family. Basically, Chris and I were old hippies. That was our ideal and it worked to some degree – for a long time, to a point. And then it didn’t work any more.

HARRY DEDICATES FACE IT to “The Girls of the Under-world.” “I was thinking of the girls from CBGB,” she says, “the musicians and people I knew like Cherry Vanilla, Helen Wheels, Wendy O. Williams [of The Plasmatics], Annie Golden [of The Shirts]. There weren’t that many women around. But it didn’t feel like competition. We were so different.” Harry stiffens slightly when reminded of the club’s infamously grotty bathroom and the lack of any private dressing space for the women who performed there. “I know what it was,” she states flatly. “I knew what I wanted to do, and that was that.”

And Harry didn’t quit even as Blondie fell apart and her relationship with Stein ended. (They broke up on the same day, in February 1987, that their friend and fan Andy Warhol died. She has never married.) Harry’s 1981 solo debut, KooKoo – produced by Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards – was notorious for H.R. Giger’s cover art, a violent about-face from Harry’s Blondie image in which he portrayed the star as a metallic automaton with skewers running through her cheeks. The LP was also a Top 10 UK hit, as was the 1986 single French Kissin’ In The USA.

Outside of Blondie, who returned in 1999 with No Exit, Harry has worked with Nick Cave and Franz Ferdinand and joined Arcade Fire on-stage at the 2014 Coachella festival. In 2015, she had a two-week residency, singing only solo material, at the Cafe Carlyle, a legendary New York cabaret room. “She’s the rare older pop artist who doesn’t need to legitimise herself with acknowledged classics,” a critic from The New Yorker wrote. “Harry could do a whole jazz show, easy, and you’d dig it.”

At SIR, asked what she hoped to achieve with the memoir, Harry simply answers, “Clarity. In that, it was a really emotional experience. Compared to today’s standards, where you’re reading everything about everybody as soon as it happens, I am too private perhaps. But I come from the era when you would ferment – let things come in. I’m not going to give it all away, right away. It’s going to ferment, for good or bad.”

Were there any particular issues or misconceptions that you wanted to clear up in Face It?

I don’t want to complain about the British press because they have been extremely good to Blondie. But for a while, they were really harping on the idea that I was Chris’s Florence Nightingale [during his illness]. That was so incorrect, so soap opera. I couldn’t deal with it. And no matter how many times I said it, it just had a life of its own.

I just thought it seemed like the normal thing to do. If you’re with a loved one – a parent, a child, a lover or husband – that’s what most of us do. We step up.

You make an example of the BBC DJ Johnnie Walker, who hammered you on that subject. [In a 2017 interview, Walker accused Harry of breaking up with Stein during his illness – “And then you walked out on him.”] It sounds like you’re still pissed off.

I thought I should mention him because he was such a pig. I haven’t really torn anybody a new asshole except him. There was no reason for him to make that assumption. And to say it twice – clearly he was trying to stick it in, give it a twist and get a rise out of me. It was pretty silly.

You write near the end of Face It, “I’ve had one fucking interesting life, and I intend to go on having one.” At this point, how does touring with Blondie, singing those songs again, fit into your idea of a future – of continuing to grow as you get older?

It is based on not being an oldies band. We are doing new material, making new records. I love what we’re doing, and I think it’s about 50/50 in the audiences. People are coming to hear the songs they know and love. Others are coming because they see the bigger picture.

I don’t want to sit around, talking about the old days. That’s not me. I have curiosity. It’s let me into some weird circumstances – and some great ones. I want to know things. I’m not the kind of person that gets all intense and crazy – “We gotta do that, we gotta go there, right now!” But if someone says, “Hey, do you want to go hang gliding?” I’m like, “Gee, I’ve never done that. I don’t know if I can. But I like the idea of soaring.”

Face It:

A Memoir

4/5

Debbie Harry

HARPER COLLINS £20

An unorthodox, occasionally shocking glimpse of the Blondie singer’s inner life.

Harry’s interviewers rarely find her keen to open up, so kudos to MOJO’s Sylvie Simmons – this snappy, chatty tome’s co-author – for guiding her so far down that path. Face It is strong on Harry’s childhood – adopted by a New Jersey couple, steeped in ’50s normalcy – with Harry attributing an enduring background unease (“I was always, always afraid”) to her abandonment, and recounting troubling early instances of sexualisation: an indecent exposure when she was eight was not the last. Harry’s quirks are manifested in a narrative that rambles liberally, photos that are augmented/defaced by scrawled text and cartoons and four sections of full-colour fan art, and while her tone is oddly cool (a shocking robbery/rape, early in Blondie’s existence, is recalled matter-of-factly), she’s good on milieu – eg, the late-’60s New York that awakened her bohemianism. A second volume is intimated but this is surely – in a good way – all the Debbie Harry you need.

Danny Eccleston